Most of us engaged in theological education in the Majority World (though not all) are “weird” in this wide world: we are Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. Our weird minds—including the electrical and hormonal systems in our brains and bodies—are fairly well-greased machines that run according to specific assumptions, rules, and ideals about how teaching and learning work and should work. The vast majority of the world thinks, feels, values, and functions differently from us in many important areas. They are likewise well-greased machines. About us:

We make up only 12 percent of the global population… Yet we are notoriously adept at making sweeping, even universalizing assumptions and applications from our own particularized set of experiences and values… [and we] unthinkingly impose our assumptions of teaching and learning on non-Western groups in missions.[1]

What happens when we place weird teachers, with all of our patterns, assumptions, and values, into non-weird learning settings? Most likely, what we are hoping to say is said—though this is not the same thing as being heard or learned!—but it is said amid various distracting noises that threaten to drown it out completely.[2] Such noise happens in so many ways: e.g., when power distances diverge, when uncertainty avoidance and acceptance clash, when long- or short-term orientation point in opposite directions, when individualism or collectivism threaten each other, when mono- or polychronicity ignore or interrupt each other. There may be few cross-cultural features wherein unwitting but distracting and hampering “noise” occurs when a print-based learner and professor seeks to guide a class of more oral-based adult students.

This article lays out some important issues asociated with orality and literacy in Majority World theological education. Many mission organizations, whether broadly focused or more narrowly focused on global theological education like my own, have not wrestled deeply or broadly enough with orality. If we do, we would be more helpful than we think we are, would like to be, and need to be. This article is geared primarily toward practitioner organizations such as the mission agency I serve and is meant to push us to be broader and deeper in our understanding of orality and literacy. The hope is that we would then seek to be even more thoughtful in our theory and practice.

1. Orality, A Primer

For decades, “orality” has been a popular term in mission circles.[3] This section will establish greater breadth and depth with a brief primer on “orality,” since histories of the various branches in the development of orality studies are found elsewhere.[4]

Some in orality studies lament that many “orality issues raised by missiologists tend not to filter down to field practitioners.”[5] Practitioners can easily act upon more shallow and narrow ideas of orality than are found in the literature. Academics also need to listen to practitioners, of course—quantitatively more and qualitatively better. Such listening would help refine their questions, definitions, observations, theories, and, thereby, suggestions. However, I am part of and primarily seek to challenge mission agencies made up primarily of practitioners, so I will focus on the first aspect. First, we should be clear on some key terms.

In general, oral learners “are people all over the globe whose mental processes are influenced primarily by spoken rather than textual forms of communication.”[6] Here are some key terms associated with “orality”:

- Literacy can refer to simple reading performance (judged to be “good enough” by some arbitrary standard), but it often refers more particularly to “the ability to understand and employ printed information in daily activities, at home, at work and in the community—to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.”[7] People who rely heavily on literature to influence their learning are often called text-based or highly print learners.

- Oral tendency or oral preference (or residual oral)[8] tend to refer to people who learn best by “receiving information and having their lives most transformed by oral methods,” even if they can read, perhaps even efficiently.[9]

- Highly oral tends to refer to people who think predominantly “by oral patterns, even though they have some exposure to literacy.”[10] Relatedly, proximal literacy refers to an increasingly common situation “in which those who cannot read have access to those who can,” as in Nehemiah 7:2–6.[11] This adds a helpful nuance to a context of high orality, as a non-literate community may be nonetheless accustomed to the influence and value of literature in their learning.

- Primary oral tends to refer to people “who cannot read or write” (some because their language has no written form) and who, thus, rely exclusively “upon oral means to remember and utilize information.”[12] This also includes people who are “totally untouched by any knowledge of writing or print.”[13]

Definitions are one thing. Understanding is another. And a key component in understanding orality, literacy, and the intersection of various versions of these in cross-cultural theological education is the idea of a spectrum or continuum with blurred lines and porous borders.

2. A Spectrum of Orality and Literacy

Randy Arnett writes:

[M]ost scholars agree that significant cognitive and sociocultural difference exists between the two poles of the oral—non-oral continuum. Assuredly, at the ends of the continuum, two identifiably distinct mentalities prevail. Yet, in practice, relatively few people cluster around the two poles. Most people are scattered along the continuum. Their position on the continuum is determined by the way they process information and perceive the world.[14]

Grant Lovejoy adds:

To the extent that people rely on spoken communication instead of written communication, they are characterized by “orality.” There are degrees of orality, depending on whether someone relies on spoken language totally or less than totally.[15]

Lynn Abney’s “Orality Assessment Tool”[16] depicts this continuum of reliance as follows:

Primary Oral—Highly Oral—Oral Tendency—Print Tendency—Highly Print

As Charles Madinger observes, orality is “a complex of how oral cultures best receive, process, remember, and replicate (pass on) news, important information, and truths.”[17] For some, it is about how comfortable they are with alternative modes of reasoning and about how much and which types of discomfort hinder rather than help their learning. For others, it is more about mentalities that are virtually nonsense to each other. There are diverse learners on the field and, thus, diverse needs within theological education.

2.1. Diverse Learners and Needs on the Field

In one classroom in the Philippines, I had students who could rely relatively equally on oral and written forms, although they were perhaps slightly more comfortable with one; students who relied more on oral forms but could learn with text-based forms—though how effectively I was not equipped to judge; and some oral-preference learners who themselves ministered to non-literate (primary oral though with proximal literacy) villagers.

Regarding the last group in my class, I was not only thinking about whether my adult students were learning effectively but about whether they were learning from me in patterns that would make their biblical and theological skills so foreign to their students that I was rendering them less effectual as teachers. As Maria asked me after class,

I have very benefited from exploring passages like Genesis 1, to circle important words and phrases about God’s ways, to underline important ideas. I know exactly who I want to teach this: six ladies in the village I minister! I am excited. But how do I help them circle and underline since they cannot read?

Maria and I briefly explored some techniques for a sort of mental exegesis that the ladies could try while listening to her read the passage aloud a few times. She left more confident and excited. But her question flagged big questions for me.

How should we deliver theological education among peoples in primary oral settings? Or in proximal literacy oral settings? Or in highly oral, or in oral-tendency, or in print-tendency with residual orality, or in highly print settings? It is easy to make blanket claims, such as “only use storytelling,” or “do not bring print, even the Scriptures, for it will create a barrier.”

However, the more nuanced and clear we can become on the precise and diverse needs of our more orally-reliant brothers and sisters, the more solid our footing will be to begin navigating andragogical issues related to orality and literacy. Take, for example, some nuances found by Herbert Klem in a field experiment he ran among the Yoruba people in Nigeria, published in 1982.[18]

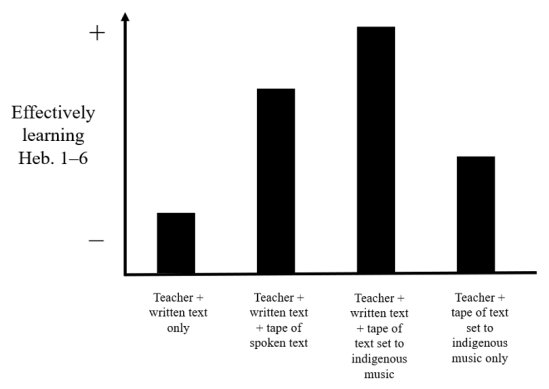

Klem sought to test effective learning and retention in the classroom by comparing the understanding of Hebrews 1–6 before and after class time. He divided the class into four groups. Within each group, half the students were oral-preference learners who could read, while half could not read. Klem used four classroom methods to compare the effectiveness for biblical learning and retention:

(1) teacher + written passage only

(2) teacher + written passage + tape of spoken passage

(3) teacher + written passage + tape of passage set to indigenous music

(4) teacher + tape of passage set to indigenous music only.

Figure 1 below shows Klem’s results. (Note: the levels in this chart are imprecise; its accuracy depends on how the groups performed in relation to each other.)

Figure 1. Compared success of styles of training in Klem’s experiment in Nigeria in 1982

A sobering insight for me is that the style that my mission agency (and many other mission agencies) has historically used is the first: teacher + written text only (Group 1), which functioned worst regarding effective learning and retention. On the other hand, I have been counseled more than once to dispose of the written text in oral settings. The reasoning has been that it adds a distracting barrier (like damaging “noise”) to their learning. Yet Klem’s study suggests that removing written text is not necessarily wise. Group 4 removed the written text and performed the second worst. Students who had a teacher and a text-tape-in-indigenous-music and the written text (Group 3) performed the best in terms of learning and retention. Even students who had a teacher and written text and a text-tape-read-out outperformed those in Group 4. That said, students in Group 4 still outperformed students with just a teacher and written text (Group 1).

How did literate students versus non-literate do in these learning groups? Did the use of written text impede their learning even if it did not for their oral-preference colleagues? There was only a minimal difference within Groups 2, 3, and 4. Only in Group 1 was there a marked difference, with literate students obviously learning and retaining it more effectively when they had a teacher and written text.

Based merely on this scratching-the-surface, limited research into the world of orality, perhaps mission agencies like my own should hold two features in tension as dual tools: the written word and the creative spoken or sung word as supplemental to our face-to-face teaching. This modest proposal even seems to be supported by Scripture—not a particular passage or theme, but its nature.

2.2. The Both/and Nature of Scripture and Implications for the Field

The Bible is a written text, and this is significant for theological education regardless of where it is engaged.[19] Also, many parts of Scripture—some more than others—bear signs of being written originally to be heard by audiences. The audiences throughout both the Old Testament and New Testament tended to be a mix of non-literate listeners with proximal literacy and oral-tendency listeners.[20] The covenant community was oral-dominated and text-dominated in different ways, and this is by God’s design.[21]

For example, Deuteronomy 6:4 says, “Hear, O Israel,”[22] and “thus says the Lord” is repeated over 400 times.[23] However, it is also important throughout the history of God’s covenant people that it is “written,” which is mentioned over 60 times in the Old and New Testaments. Indeed, listen to—wait, I mean read—God’s commanded dynamic between written and oral modalities after Moses’s arms were held up against Amalek: “Write this as a memorial in a book and recite it in the ears of Joshua, that I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven” (Exodus 17:14, ESV). God later commands Moses: “Now write down this song and teach it to the Israelites and have them sing it, so that it may be a witness for me against them” (Deuteronomy 31:19 NIV). What with the Ten Words written by God’s own hand (Exodus 31:18) and the laws meant to be written in a book by Moses and read to the people (Exodus 24:3–7; cf. Deuteronomy 31:9–13), God built his entire rescued covenant community with a dynamic of text and orality.[24] God’s pattern continues in the new covenant,[25] as his people naturally navigated a society with oral, scribal, rhetorical, reading, and literary subcultures intertwined dynamically.[26]

Scripture itself, thus, portrays a complex “interconnectedness of oral and written dimensions”[27]—an “oral/written interface.”[28] This implies two challenges for us theological educators: interpretation and teaching. First, anyone who seeks to interpret these sacred texts without reference to hermeneutical maneuvers specifically associated with orality (overlapping yet also distinct from text-based hermeneutics) is likely to misunderstand some of the original meaning, intent, and effect of the text itself.[29] Second, neither oral nor written dimensions should be discounted in our teaching of Scripture at all, especially when we train Christian leaders who have a blend of qualities somewhere on the oral-tendency/print-tendency spectrum. It would be wise to bring together “an integration of the strengths of oral and printed methodologies.”[30] The nature of Scripture itself suggests this.

In this article, so far, we have explored some features of the orality spectrum, including implications for a more carefully thought-out combination of oral and written methodologies—both in our teaching and in our interpretation of Scripture itself. But we are far from having a wider and deeper understanding of what is going on in more oral-reliant learners. We now turn to that so that the Majority World theological education in which we engage might be more effective.

3. Thinking More Broadly about Orality

Many print-based practitioners hear “orality” and think “storytelling” and “Bible storying.”[31] It is certainly the case that “storying” or “storytelling” are helpful tools, that is, for some oral-tendency learners in some places. However, since much thought has been given to developing tools such as “Chronological Bible Teaching,”[32] we do not need to explore it here.

W. Jay Moon gives a commendation and a challenge pertinent to our present focus on the breadth of orality:

Mission organizations and academic institutions that are developing and applying storytelling methods/courses are to be commended. While this is a good start, it is simply the tip of the iceberg. Equal attention should be given to other oral genres.[33]

Orality and storytelling are not coterminous. This matters, not least because it is not broad enough to meet the diversity of global learning needs among more oral peoples.

Take Kazakhs as an example. Erik Aasland observes that “the traditional resource for defining problems, making moral judgments and suggesting remedies” is the proverb.[34] Proverbs function more powerfully than the stories themselves,[35] although it is often best when the two forms work together: a well-crafted proverb delivering the lingering punchline of a story.[36]

According to Samuel Chiang and William Coppedge, various forms (or genres) of oral processing and transmission can be found in ballads (often putting narrative to song) and dance as well as storytelling and proverbs.[37] Tom Steffen recognizes the interaction of story with symbol and ritual in shaping the worldview of oral-preference learners.[38] Randy Arnett includes drama, visual literacy, testimonies, folktales, and poems.[39] David Clark adds epic.[40] Jay Moon adds dance and apprenticeships.[41] Paul Hiebert adds aphorisms, riddles, creeds, and catechisms.[42] Lynn Thigpen highlights these additional oral learning media: kinesthetic, social, observational, ceremonies, hymns, experience, dreaming, elders, creative arts, popular theatre, drumming, village criers, orators, memory work, recitation, chanting of monks, and rote learning.[43] Orality is significantly broader than Bible storying or storytelling in general.

Many of these oral genres can also be expressed in a breadth of ways, in “multimodal” and “multiplex” manners.[44] They can be:

Read, recited, sung, cantillated, chanted, declaimed, multimodally performed, communicated through audio recordings or the web, experienced in the sonic memory. They can be individually or collectively enacted, informal or liturgical, public or private, announcements by one person or dialectical engagement.[45]

It should be clear that “equating orality to oral storytelling is drastically incomplete.”[46] This should have implications for theological education.

A nuance is worth adding. While there are many forms of oral communication and learning other than storytelling, orality is about “more than story” in a different way too.[47] As Chiang and Coppedge maintain:

An argument can be made that story is inherent in all oral communication. For example, many proverbs are but the synopsis of a larger story; similarly, song often invites us into a narrative, whether of love, loss, or worship. Drama is narrative-based, and dance is often the physical embodiment of a cultural narrative. These examples are more than story; however, story often plays an essential role in their development. Story, therefore, is the life-blood of orality… [though] equating orality to oral storytelling is drastically incomplete.[48]

Indeed, any biblical interpreter who pursues the historical reason(s) why an author wrote an epistle (for instance) as part of their interpretation of the letter itself should recognize that “story” itself (in the sense of sequential, cause-and-effect happenings) is important to even non-narrative texts.

Sadly, as Arnett observes, even “a cursory survey of available web-based literature reveals a plethora of information and training on story[telling], but a paucity of information on other aspects of orality.”[49] This affects practitioner-dominant mission organizations like ours. Not least, we have not filled the important position of Director of Orality because everyone who applied has been too narrowly focused on storytelling and only the narrative portions of Scripture. As helpful as that sliver of orality is in some oral settings for some oral peoples, the diversity of needs in the field where we engage pastors and other Christian leaders is simply too multifaceted for that narrowness.

Furthermore, God himself uses a breadth of communicative techniques in Scripture. He inspired much narrative, of course; and poem, and ritual, and proverb, and genealogy, and law, and symbol, and song, and wisdom, and letter, and apocalypse. God has always used a breadth of diverse forms to guide his oral, oral-preference, and textual people ever deeper into the “story” of how he is displaying his goodness and glory to creation through humans, particularly by reconciling the world to himself under King Jesus.

Regarding orality, we must equip ourselves and each other broadly. Only then can we be more effective in guiding the learning and worship of beloved brothers and sisters, regardless of which oral forms are the most pervasive and powerful for deep learning in their given context. But we also must consider orality more deeply.

4. Thinking More Deeply about Orality

Simultaneously with lacking breadth, many practitioner mission agencies of theological education in the Majority World, like my own, show a lack of depth in understanding orality. This manifests readily when we feel satisfied with merely tweaking our normal practice, perhaps in light of an article on orality or a conference paper. Therefore, we now use a farming metaphor instead of our normal industrial one. We now illustrate with soccer, even calling it “football” (because we are culturally sensitive), instead of with American football. Instead of drawing a coniferous fir tree on the chalkboard as an archetypal tree, we draw an umbrella thorn tree when in Tanzania.

Such surface tweaking and tinkering are good; keep them up! The problem is when we just stop there. There are much deeper issues at stake. While our “pragmatic teaching strategies attempt to be culturally sensitive,” we “have yet to address how oral adults learn.”[50] Such illustrations and stories remove some small barriers—which is not harmful—but they do not get down to “the conceptual structures and schemata of oral-background people.”[51] What we need is “‘an overall reconceptualization of the education’ of this type of learner.”[52]

4.1. The God-designed Learning Brain

First, we should not be surprised to hear of differences in “conceptual structures and schemata” and in thinking, reasoning, memory, etc. among the diversity of humanity. Learning to read itself seems to impact patterns of processing information (e.g., as shown among Siberian Ichkari women).[53] According to Yoakum, “Social, economic, and geographical factors influence the development of a society’s cognitive habits in addition to literacy.”[54] And as Brad Strawn and Warren Brown observe,

What emerges in the cognitive operations of the hypercomplex physical system of a human is conditioned by the physical, social, and cultural environment in which it is embedded… [The mind itself] forms its capacities, gains knowledge of the world, and organizes itself through interactions with the world it occupies.[55]

Thinking concretely, suppose an adult student’s community mainly engages in various oral media for learning, with little to no reading for learning, while their visiting professor’s community regularly engages the written medium as a major aspect of learning. Both have been embedded in such environments at home from birth and in various forms of community life through their formative and educational years (e.g., parenting, social gatherings, school, church)—not to mention for generations. Drop one into the other’s context and tell them to engage in teaching and learning. Such different and deeply embedded patterns, assumptions, values, and practices will not mesh naturally—and certainly not quickly, forged as they were over the long haul. However, the differences run even deeper than habit.

As Jay Moon notes, “Recently, neurologists have used imaging studies to demonstrate that the brain is actually rewired differently when someone learns to read.”[56] A body of corroborating findings continues to grow and deepen, showing that “literacy-induced neuroplasticity” results in various types of “reorganization” in different parts of the brain important to learning.[57] Douglas Fields writes, “Learning a wide range of skills”—e.g., “reading, abstract intellectual learning, including classroom study… is associated with structural changes in appropriate cortical regions or fiber tracts.”[58] The neural wiring and structure of the brain change with different educational practices, including reading itself. And “the brain that is produced” within and by a certain environment and society will “maximize success” under similar conditions. For the brain, it matters—for gray matter, white matter, and much underneath[59]—whether reading and certain associated patterns of thought are or are not fundamental nor indeed constitute any part of deep and transformative learning.[60]

Do not miss this: people in all learning environments have different aspects of our brains stimulated or not, activated or not, myelinated or not, and developed or underdeveloped due to patterns of use and non-use. We all have patterns of brain density and gaps and strong and weak neural tracts and circuits due to how learning works, is valued, and is encouraged and nurtured in our respective environments. This feature of God’s creation simply makes crossing boundaries with “our” version of education more difficult and complex at strikingly deeper levels than most of us have considered when we rush in and just do it—and it should make us humble.

Still, in God’s creative providence, there is also good news for all on the oral–non-oral continuum: brains can be wired and rewired! Neuroplasticity is alive and well throughout life and the world.[61] Indeed, learning itself is in part “based on neuroplasticity, i.e., on the capability of the brain to adapt to new experiences.”[62] New neural pathways and circuits are constantly (though slowly) being cut, connected, myelinated, and networked. This is a deep aspect of learning. But there is still more.

4.2. Patterns of Expression and Thought

A surge in research on orality came in 1982 with Walter Ong’s publication of Orality and Literacy.[63] Research has gone well beyond Ong’s study, of course, at some points even in opposition to his ideas.[64] But he did establish or solidify certain categories and ideas that we must still consider when wrestling with orality, literacy, and theological education.

For example, which of these four items would you exclude from the cluster as the one that does not belong: axe, hammer, wood, saw? People in print-based learning cultures tend (though not without exceptions) to say that wood does not belong. It’s obvious, right? It’s the only one that is not a tool! People in oral-based learning cultures tend (not without exceptions) to say that the hammer clearly does not belong. It’s obvious, right? Axes and saws are meaningless without wood, so axes, saws, and wood clearly go together. Who ever heard of using a hammer on wood?! How silly.

Everyone’s mind categorizes. One explanation is categorizing based on abstract qualities, thinking of belonging in terms of tools versus material. The other is categorizing based on practical uses, thinking of belonging in terms of what are actually used together in life.

Such divergent patterns of mental tendencies lead scholars to say that oral-based and print-based learners “store information differently.”[65] We “process information and perceive the world” differently.[66] This adds complexity to that oral–non-oral continuum described above. Orality-literacy is not just about the quantitative degree of reliance on relationships and reading. For one, information storage—whether in active memory or written (and thus semi-permanent) form—is not in the same parts of the mind (whether in the brain or our extended cognition).[67] For another, abstraction and function are not merely two points on a qualitatively similar spectrum; they are qualitatively different patterns of thought. And there is more.

According to Steffen and Bjoraker, oral learners tend not only to “prefer to learn through oral means” but also tend to “think holistically and more circularly (in contrast to linearly), remember visually, and prefer to communicate concretely and affectively.”[68] Here I will present three different but overlapping schemes that capture aspects of the thought patterns of more oral-reliant learners and more print-reliant learners.

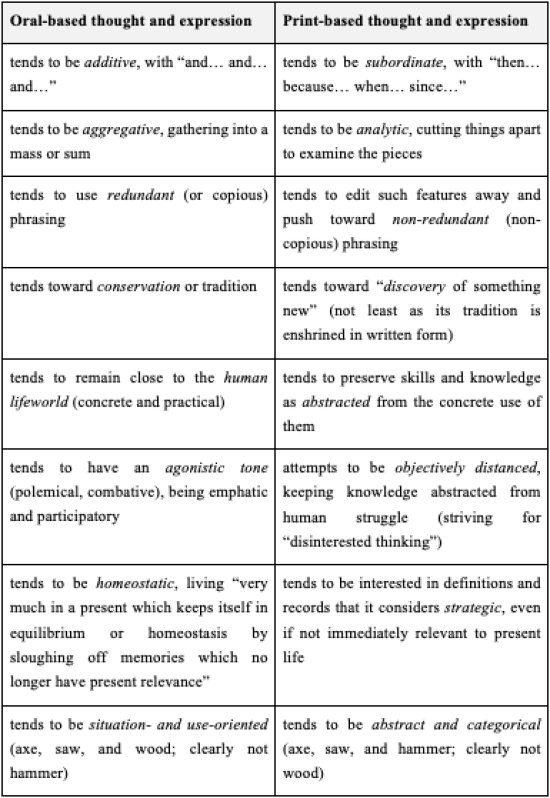

First, Ong’s famous chapter on “psychodynamics of orality” in Orality and Literacy explores some perceived differences between oral-based and print-based thought and expression. If he is even partly correct in seeing such patterns (allowing for plenty of exceptions in various types of oral communities, of course), we would do well to consider implications for curriculum design and classroom interaction as we read the comparison chart below.

Figure 2. Oral-based vs. print-based thinking and expressing (Ong)

All of these elements have a healthy place in learning and life. Different cultures tend to move in different directions and with different emphases. Issues come not least when those of us with authority (professors) unwittingly neglect some elements where they would be the most appropriate and over-emphasize other elements, when we unthinkingly assume that our impulses and patterns are always best (or at least typically better), and when we uncritically ignore or refuse others’ impulses and patterns, especially on their own turf and ministry space.

Second, we can also benefit from Victor Turner’s work in The Ritual Process.[69] W. J. Moon gives a helpful summary, using the acronym CHIMES to capture some key elements of primary oral and oral-tendency learners.[70] Just as with Ong’s list, so too here: none of these holds in each case without exception. But as a general pattern, our brothers and sisters on the more oral side of the learning spectrum tend to be more:

- Communal—learning from each other in a group.

- Holistic—with each area of life affected by the learning.

- Image-oriented—with symbols and object lessons stretching beyond words.

- Mnemonic-oriented—with formulaic devices and even genres “hooking” learning and later “triggering” memory.

- Experiential—learning about what is immediately connected to real life.

- Sensory—learning about what engages multiple senses.

To be sure, all of these learning elements of CHIMES ring true of what would benefit more text-reliant learners too; “weird” education tends to undercut its own effectiveness not least through hyper-individualism and an imbalanced focus on cognition and content-dumping lectures.[71]

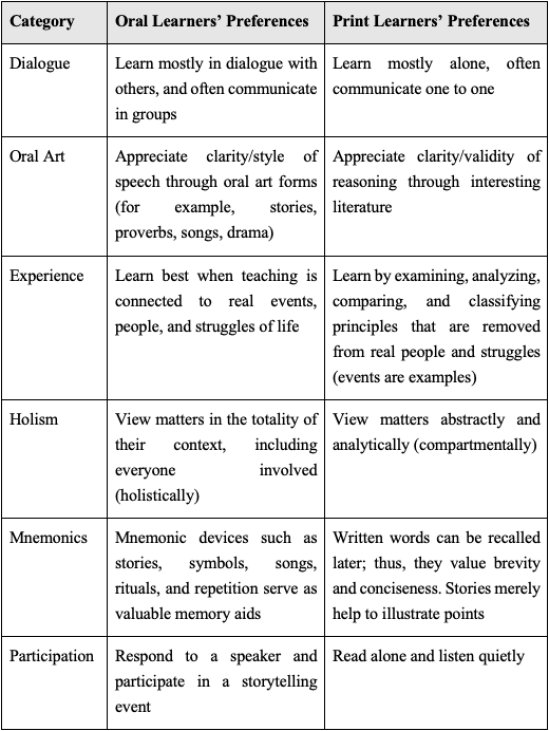

Third, Moon himself compares oral and print learning under the categories of dialogue, oral art, experience, holism, mnemonics, and participation. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Oral versus Print Learning Preferences (W. J. Moon)

I hope these three lists of significant differences between oral- and print-based learning (Ong, CHIMES, and Moon) trigger a desire to dig in more deeply (as well as more broadly) into orality. It will help our engagement in Majority World theological education, particularly in more oral-reliant cultures.

5. Conclusion

The great and small differences between learners along the oral–print spectrum suggest different needs on the field of global theological education. As Moon writes,

Missionaries involved in theological education/training need to understand and adjust to the deep differences in oral versus print learners. In particular, reflection on how oral learners receive, reason through, remember, and then re-create messages should alter pedagogical approaches to theological education worldwide.[72]

Indeed.

Even when we only focus on the orality–literacy spectrum and set aside other crucial cultural categories—e.g., power distance, individualism or collectivism, uncertainty avoidance or acceptance, long- or short-term bents, mono- or polychronicity—there cannot be a one-size-fits-all program of theological education. The needs across God’s world are broader than that. And the morphing or overhauling of programs and their implementation on the field cannot merely contain surface shifts. We must go deeper than many of us realize.

[1] Jonathan Worthington, “Mature Together: The Task of Teaching in Missions,” Desiring God Featured Article Initiative (March 22, 2022), https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/mature-together.

[2] Kathleen Verderber, Rudolph Verderber, and Deanna Sellnow, Communicate! 14th ed. (Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2014), 12. See Tom Steffen, Worldview-based Storying: The Integration of Symbol, Story, and Ritual in the Orality Movement (Richmond: Orality Resources International, 2018), 19.

[3] “Orality” is not the same as an auditory learning style in America. In print-based societies like the USA, our systems of learning have been based in written texts for generations, and while an American’s auditory learning style (as distinct from visual or tactile/kinesthetic) overlaps with learning in “oral” cultures, there are profound differences in patterns of thought, information storing, and organization, etc. See W. Jay Moon, “Fad or Renaissance? Misconceptions of the Orality Movement,” International Bulletin of Mission Research 40.1 (2016): 6–21, esp. 9–10.

[4] See Steffen, Worldview-based, 32–113; Trevor Yoakum, “The Spoken Word: God, Scripture, and Orality in Missions,” Ph.D. diss., Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2014; Lynn Thigpen, Connected Learning: How Adults with Limited Formal Education Learn (Eugene: Pickwick, 2020).

[5] Randy Arnett, “Discipleship in the Face of Orality,” Orality Journal 6.1 (2017): 49–58, 52.

[6] See the International Orality Network (ION): https://orality.net/about/who-are-oral-learners-original-graphics/. There is some value (heuristic certainly, and perhaps more) in speaking of oral and print learners as learning from people vs. from print, respectively (Thigpen, Connected Learning). I’m not convinced this is precise enough, e.g., print-learners conceive of their text-learning as being from people: “According to Thigpen,” “As Steffen explains.” It’s not about print per se. More precise might be dynamic and immediate vs. static or slow (if an author responds), or holistic relational vs. particular relational.

[7] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Literacy in the Information Age: Final Report of the International Adult Literacy Survey (Paris: OECD Publication Service, 2000), x–xi. The language of “one’s goals” and “one’s knowledge and potential” does not have to be interpreted individualistically; in collectivist cultures “one’s” goals and potential can be conceived of as inseparable from the societal unit. Also, the OECD distinguishes the domains of “prose literacy,” “document literacy,” and “quantitative literacy.” We are focused on literacy within the world of biblical and theological studies; therefore, the “prose literacy” domain of literacy skills is most pertinent.

[8] Yoakum, “Spoken.”

[9] Moon, “Fad,” 12.

[10] Moon, “Fad,” 12.

[11] Thigpen, Connected, 115.

[12] W. Jay Moon, “Understanding Oral Learners,” Teaching Theology and Religion 15.1 (2012): 29–39, see 30.

[13] Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World (London: Routledge, 1982), 11.

[14] Arnett, “Discipleship,” 50.

[15] Grant Lovejoy, “The Extent of Orality,” JBTM 5.1 (Spr 2008): 122 (emphasis added according to his wider writing).

[16] Lynn Abney, “Orality Assessment Tool” (2001), based on Ong’s Orality and Literacy, found at https://story4glory.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Orality_Assessment_Tool_Worksheet1.pdf.

[17] Charles Madinger, “Coming to Terms with Orality: A Holistic Model,” Missiology: An International Review 38.2 (2010): 201–12, 205; cf. Madinger, “A Literate’s Guide to the Oral Galaxy, Part 1,” Orality Journal 2.2 (2013): 13–40, 15.

[18] Herbert Klem, Oral Communication of the Scripture: Insights from African Oral Art (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 1982). For Klem’s place within the Orality Movement, see Steffen, Worldview-based, 66–67.

[19] William Coppedge, “African Literacies and Western Oralities? Communication Complexities, the Orality Movement, and the Materialities of Christianity in Uganda,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Edinburgh (2019).

[20] Cf. John Harvey, Listening to the Text: Oral Patterns in Paul’s Letters, ETS Studies Series 1 (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1998); Joanna Dewey, ed., Orality and Textuality in Early Christian Literature (Atlanta: SBL, 1994). Even if many in the original audiences were completely non-literate, they nevertheless knew about writing and saw its societal value (hence proximate literate), not least for their cultural leaders of priests and kings (and prophets?) and scribes.

[21] See the language of “dominant” in Tom Steffen and William Bjoraker, The Return of Oral Hermeneutics: As Good Today as it was for the Hebrew Bible and First-Century Christianity (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2020), 136. Rosalind Thomas warns Classicists against seeing “a literate or an oral society according to [one’s] predominant interests or tastes (Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece [Cambridge: CUP, 1992], 4). This is also applicable to missiologists.

[22] Some observe that Moses does not say, “Read, O Israel,” and seek to infer the oral nature of the crowds. While most within the crowds likely could not read, Moses would have said “Hear” in a speech to a crowd even of highly-print learners. See Stanley Porter and Bryan Dyer, “Oral Texts? A Reassessment of the Oral and Rhetorical Nature of Paul’s Letters in Light of Recent Studies,” JETS 55.2 (2012): 323–41, see 332.

[23] Steffen and Bjoraker, Return, 136.

[24] David Carr argues that rather than being written to be “incised and read on parchment or papyrus,” the Scriptures were written to “enculturate ancient Israelites—particularly Israelite elites—by training them to memorize and recite a wide range of traditional literature” in order to educate primary oral or oral-tendency disciples (Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature [Oxford: OUP, 2008]; cf. Steffen and Bjoraker, Return). In the New Testament era, a certain prominent and well-respected biblical and political leader among the Jewish communities of Alexandria, Egypt, Philo, did not have such a dichotomy as Carr (above). Philo very much “incised and read on parchment and papyrus” and taught others to do likewise. (See Jonathan Worthington, “Use of the Old Testament in Philo,” in D. A. Carson, Greg Beale, Andy Naselli, and Ben Gladd, eds., Dictionary of the New Testament’s Use of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2023), forthcoming.) This does not assert that Philo was right; but it does caution us from saying that New Testament authors held Carr’s perspective rather than a contemporary’s (unless data proves otherwise).

[25] Compare “ears” and “hear” in Matt. 13:9 with “written” in 12:3–5, and compare “write” and “scroll” in Rev. 1:3, 11, 19; 2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 14; 22:7, 9, 10, 18, 19 with “ears” and “hear” and “says” in 1:3; 2:7, 11, 17, 29; 3:6, 13, 22; 22:18.

[26] Vernon Robbins, “Oral, Rhetorical, and Literary Cultures,” Semeia 65 (1994): 75–90.

[27] Lourens de Vries, “Views of orality and the translation of the Bible,” Translation Studies 8.2 (2015): 141–55; cf. Steffen and Bjoraker, Return; Russ Resnik, “Oral Hermeneutics: A Conversation with Bill Bjoraker,” Kesher (2021).

[28] Carr, Writing.

[29] Steffen and Bjoraker, Return.

[30] Samuel Chiang and William Coppedge, “Connecting Orality, Language, and Culture,” Orality Journal 6.1 (2017): 7–11, 9.

[31] For an example of this mistake, see this well-made 1:31-minute publicity video: https://orality.net/content/proclaiming-the-good-news-through-story-in-oral-cultures/.

[32] See the many helpful resources at the International Orality Network (ION) here: https://orality.net/; J. Terry, Basic Bible Storying: Preparing and Presenting Bible Stories for Evangelism, Discipleship, Training, and Ministry (Fort Worth: Church Starting Network, 2008); Tom Steffen, Reconnecting God’s Story to Ministry: Crosscultural Storytelling at Home and Abroad (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2005).

[33] Moon, “Fad,” 17.

[34] Erik Aasland, "Exploring the Links Between Kazakh Proverbs and Kazakhstani Societal Movements," Anthropology News 55 (2014): 36-86, https://www.academia.edu/3412908/Kazakh_Proverbs_and_Kazakhstani_Societal_Movements.

[35] See the work of Erik Aasland accessible at https://fuller.academia.edu/ErikAasland, in particular Aasland, "Contrasting Two Kazakh Proverbial Calls to Action: Using Discourse Ecologies to Understand Proverb Meaning-Making," Proverbium: The Yearbook of Annual Proverb Scholarship 35 (2018): 10-14, https://www.academia.edu/37111691/Contrasting_Two_Kazakh_Proverbial_Calls_to_Action_Using_Discourse_Ecologies_to_Understand_Proverb_Meaning_Making.

[36] Erik Aasland, "Two Heads are Better Than One: Using Conceptual Mapping to Analyze Proverb Meaning," Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 26 (2009): 1-18, https://www.academia.edu/358767/Two_Heads_are_Better_Than_One_Using_Conceptual_Mapping_to_Diagram_Proverb_Meaning.

[37] Chiang and Coppedge, “Connecting,” 8.

[38] Steffen, Worldview-based. Cf. Victor Turner on symbol as a connector of sensory experience and ideology and as a precursor or building block for rituals: The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 1995).

[39] Arnett, “Discipleship,” 51. Cf. the story of discovery in the history of the International Orality Network: https://orality.net/about/ion-history/how-we-began/.

[40] David J. Clark, “Oral Communication of the Scripture,” Indian Journal of Theology 33 (1984): 66–76, 67. Cf. Moon, “Fad,” 8–9.

[41] Moon, “Fad,” 10.

[42] Cf. Paul Hiebert, Anthropological Insights for Missionaries (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1985); Paul Hiebert, Daniel Shaw, and Tite Tiénou, Understanding Folk Religion: A Christian Response to Popular Beliefs and Practices (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1999); and Paul Hiebert, Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008).

[43] Thigpen, Connected, 44–7.

[44] Ruth Finnegan, “Orality and Literacy: Epic Heroes of Human Destiny?” International Journal of Learning 10 (2003): 1551–60.

[45] Ruth Finnegan, “Response from an Africanist Scholar,” Oral Tradition 25 (2010): 7–16, 9; Thigpen, Connected, 48.

[46] Chiang and Coppedge, “Connecting,” 8 (emphasis added).

[47] Tom Steffen, “Orality Comes of Age: The Maturation of a Movement,” International Journal of Frontier Missiology 31.3 (Fall 2014): 139–47, 142–43.

[48] Chiang and Coppedge, “Connecting,” 8 (emphasis added).

[49] Arnett, “Discipleship,” 52.

[50] Thigpen, Connected, 49 (emphasis added).

[51] Arnett, “Discipleship,” 52 (emphasis added).

[52] Andrea DeCapua and Helaine W. Marshall, “Serving ELLs with Limited or interrupted Education: Intervention that Works,” TESOL Journal 1 (2010): 49–70, 51; flagged and quoted in Thigpen, Connected, 49.

[53] Aleksandr Luria, Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976). Cf. Lev Semyonovitch Vygotsky, Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, ed. Michael Cole et al. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978); Yoakum, “Spoken,” 51–2, 74–75.

Ong suggested that this was the case (Orality, 50). Thigpen’s critique of him at this point (Connected, 37) is misplaced as she uses neuroscience studies to throw doubt on Ong’s supposition, though one study does not critique what Thigpen thinks it critiques (so Maria Dias et al., “Reasoning from Unfamiliar Premises: A Study with Unschooled Adults,” Psychological Science 16 [2005]: 550–54) and the other actually supports Ong’s supposition (so Mary H. Kosmidis et al., “Semantic and Phonological Processing in Illiteracy,” Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 10 [2004]:818–27; cf. Alfredo Ardila et al. [including Kosmidis], “Illiteracy: The Neuropsychology of Cognition without Reading,” Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 25 [2010]: 689–712).

[54] Yoakum, “Spoken,” 74.

[55] Brad Strawn and Warren Brown, Enhancing Christian Life: How Extended Cognition Augments Religious Community (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2020), 44.

[56] Moon, “Fad,” 10. Cf. Kosmidis et al., “Semantic,” 818–27; Ardila et al., “Illiteracy,” 689–712.

[57] Michael A. Skeide et al., “Learning to read alters cortico-subcortical cross-talk in the visual system of illiterates,” Science Advances 3.5 (2017): 817–23. Compare how the pulvinar, which is affected by learning to read (Skeide et al.), has a role in such learning skills as attention, memory, and decision-making (Jorge Jaramillo et al., “Engagement of pulvino-cortical feedforward and feedback pathways in cognitive computations,” Neuron 101 [2019]: 321–36 [see Fiebelkorn and Kastner, “The Puzzling Pulvinar,” for a helpful summary of Jaramillo et al.]; cf. Y. Komura et al., “Responses of pulvinar neurons reflect a subject’s confidence in visual categorization” Nat. Neurosci 16 [2013]: 749–55).

[58] R. Douglas Fields, “Imaging Learning: The Search for a Memory Trace,” The Neuroscientist 17.2 (2011): 185–96, 185; cf. Fields’ work on myelination and related brain development in “Genius across Cultures and the ‘Google Brain,’” Scientific American (Aug 20, 2011); “White Matter Matters,” Scientific American 298.3 (2008): 54–61. Cf. J. Moon, “Encouraging Ducks to Swim: Suggestions for Seminary Professors Teaching Oral Learners,” William Carey International Development Journal 2.2 (2013): 3–10, 4.

[59] Marco Taubert, Arno Villringer, and Patrick Ragert, “Learning-related gray and white matter changes in humans: an update,” Neuroscientist 18.4 (2012): 320–25; cf. Fields, “White Matter Matters.”

[60] Fields, “Genius.”

[61] Functional and structural brain plasticity is possible throughout life, not only in childhood and adolescence, as was previous thought (Taubert et al., “Learning-related,” 320–25; B. Draganski and A. May, “Training-induced structural changes in the adult human brain,” Behav. Brain Res. 192.1 [2008]: 137–42). That said, the insights above from Fields about the limited developmental periods of myelin development are still important.

[62] T. Schmidt-Wilcke et al., “Distinct patterns of functional and structural neuroplasticity associated with learning Morse code,” Neuroimage 51.3 (2010): 1234–41, 1234.

[63] Ong had significant predecessors, and important aspects of what has become the “Orality Movement” in certain evangelical mission circles developed slightly before and seemingly apart from such academic work. See Steffen’s charting of the three streams within the development of orality studies and experiments in Worldview-based, 32–113. Cf. Jack Goody, The Interface between the Written and the Oral (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

[64] E.g., Thigpen (Connected) and Yoakum (“Spoken”) strongly critique a mono-directional, simplistic notion of the evolution from orality to literacy (the “unilinear evolutionary theory”) and patterns of thinking accompanying both, a notion attributed to the Toronto School of Communication that included Harold Innis, Eric Havelock, Marshall McLuhan as well as Ong. Other critiques of Ong incur debate even among scholars who agree against Ong on the aforementioned issue. For example, Thigpen critiques Ong for having a one-size-fits-all approach for how oral people or textual people learn and communicate, but Yoakum suggests that this would be a misreading of Ong.

[65] Arnett, “Discipleship,” 51.

[66] Arnett, “Discipleship,” 50.

[67] Strawn and Brown, Enhancing.

[68] Steffen and Bjoraker, Return, 72.

[69] Turner, Ritual.

[70] Moon, “Fad,” 10.

[71] See Jonathan Worthington, “Deep Motivation in Theological Education,” Themelios 45.3 (2020): 620–37; “Deep Learning that Transforms,” Training Leaders International, 2021; “The Path of Deep Learning,” Training Leaders International, 2023 (forthcoming).

[72] Moon, “Fad,” 17.